(C) 2013 Helen R. Bayliss. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC-BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For reference, use of the paginated PDF or printed version of this article is recommended.

Citation: Bayliss HR, Stewart GB, Wilcox A, Randall NP (2013) A perceived gap between invasive species research and stakeholder priorities. NeoBiota 19: 67–82. doi: 10.3897/neobiota.19.4897

Information from research has an important role to play in shaping policy and management responses to biological invasions but concern has been raised that research focuses more on furthering knowledge than on delivering practical solutions. We collated 449 priority areas for science and management from 160 stakeholders including practitioners, researchers and policy makers or advisors working with invasive species, and then compared them to the topics of 789 papers published in eight journals over the same time period (2009–2010). Whilst research papers addressed most of the priority areas identified by stakeholders, there was a difference in geographic and biological scales between the two, with individual studies addressing multiple priority areas but focusing on specific species and locations. We hypothesise that this difference in focal scales, combined with a lack of literature relating directly to management, contributes to the perception that invasive species research is not sufficiently geared towards delivering practical solutions. By emphasising the practical applications of applied research, and ensuring that pure research is translated or synthesised so that the implications are better understood, both the management of invasive species and the theoretical science of invasion biology can be enhanced.

Alien species, biological invasions, knowledge transfer, research evaluation, science policy

Access to scientific information is important in ensuring an effective response to biological invasions (

The IUCN Red List database implicates invasive species in the extinction of more than half of the 170 species for which data are available (

We gathered priorities for science and management from members of the international invasive species community using a combination of methods to increase participation. Hard-copy questionnaires designed to assess information use by invasive species stakeholders were distributed at two events in Great Britain; the GB Non-Native Species Secretariat Stakeholder Forum 2009 and the British Ecological Society Invasive Species Group Conference 2009. Questionnaires were anonymous, but respondents were asked to identify their main area of responsibility (i.e. research, policy, practice, others). The questionnaires finished with a question asking respondents to identify their three top priorities for invasive species science and management. The same question was distributed to delegates attending a dedicated workshop held at the European Congress of Conservation Biology in Prague, 2009. In 2010, the question was included in an anonymous electronic questionnaire exploring information selection and sharing that was distributed to the international invasive species community using the Aliens-L email list of the Invasive Species Specialist Group of the IUCN Species Survival Commission and subsequently reposted onto other web pages and email lists by recipients. Responses from the questionnaires and the workshop were entered into a spread sheet for thematic analysis, whereby related priorities were grouped using an iterative process (see online Appendix I: Stakeholder priorities for the data used in the analyses). Priorities were also analysed by comparing responses between stakeholder groups, with the eight most frequently identified priorities (those identified a total of twenty or more times) charted to allow comparison by stakeholder group.

We then undertook a search of eight journals likely to publish research of broad relevance to invasion biology. Four journals were ‘traditional’ ecological journals; Biological Invasions; Diversity and Distributions; the Journal of Applied Ecology; and Trends in Ecology and Evolution. The other four were subsequently selected to broaden the scope of the study, and included Ecological Economics, Journal of Environmental Management, Weed Research and Conservation Evidence. Other relevant journals which did not cover the time period of 2009–2010 (such as Management of Biological Invasions or NeoBiota, which produced their first issues in 2010 and 2011 respectively) or those which were specific to a particular group or biome (such as Aquatic Invasions) were not included. We collected all articles relating to biological invasions that were published in the eight journals during 2009 and 2010 (the same period as the priorities were gathered) except letters to the editors, obituaries, book reviews and errata, which were not included in the assessment. Papers were classified using the main theme described in the title, or using the abstract when this was not clear. We attempted to classify all of the articles against the same thematic groups that had been identified from the priorities, but as many papers related to more than one priority area or covered different topics, the thematic groups were revised using an iterative process to better reflect the nature of the articles collected. Each paper was classified against only one main topic area (see online Appendix II: Journal article classifications for the data used in these analyses).

The priorities and research topics were compared using odds ratios (

197 individuals responded to the different questionnaires (Table 1). Of these, 159 respondents provided a total of 449 individual priorities. Respondents represented a range of stakeholder groups; the main being researchers (40.5% of respondents providing priorities), practitioners (24.0%), and policy makers and advisors (20.3%). Respondents from other stakeholder groups such as volunteers or knowledge brokers accounted for 15.2% of respondents.

The number and type of respondents each providing up to three priorities for invasive species science and management through questionnaires deployed at two events in 2009 and electronically in 2010.

| Source | GB hard-copy questionnaires, 2009 | Workshop at ECCB Conference, Prague, 2009 | International electronic questionnaire, 2010 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total no. respondents | 41 | 18 | 138 | 197 |

| No. providing priorities | 37 | 17 | 104 | 158 |

| No. working in research | 9 | 14 | 41 | 64 |

| No. working in practice | 15 | 0 | 23 | 38 |

| No. working in policy | 11 | 3 | 18 | 32 |

| No. of other stakeholders | 2 | 0 | 22 | 24 |

| Total priorities supplied: | 98 | 48 | 303 | 449 |

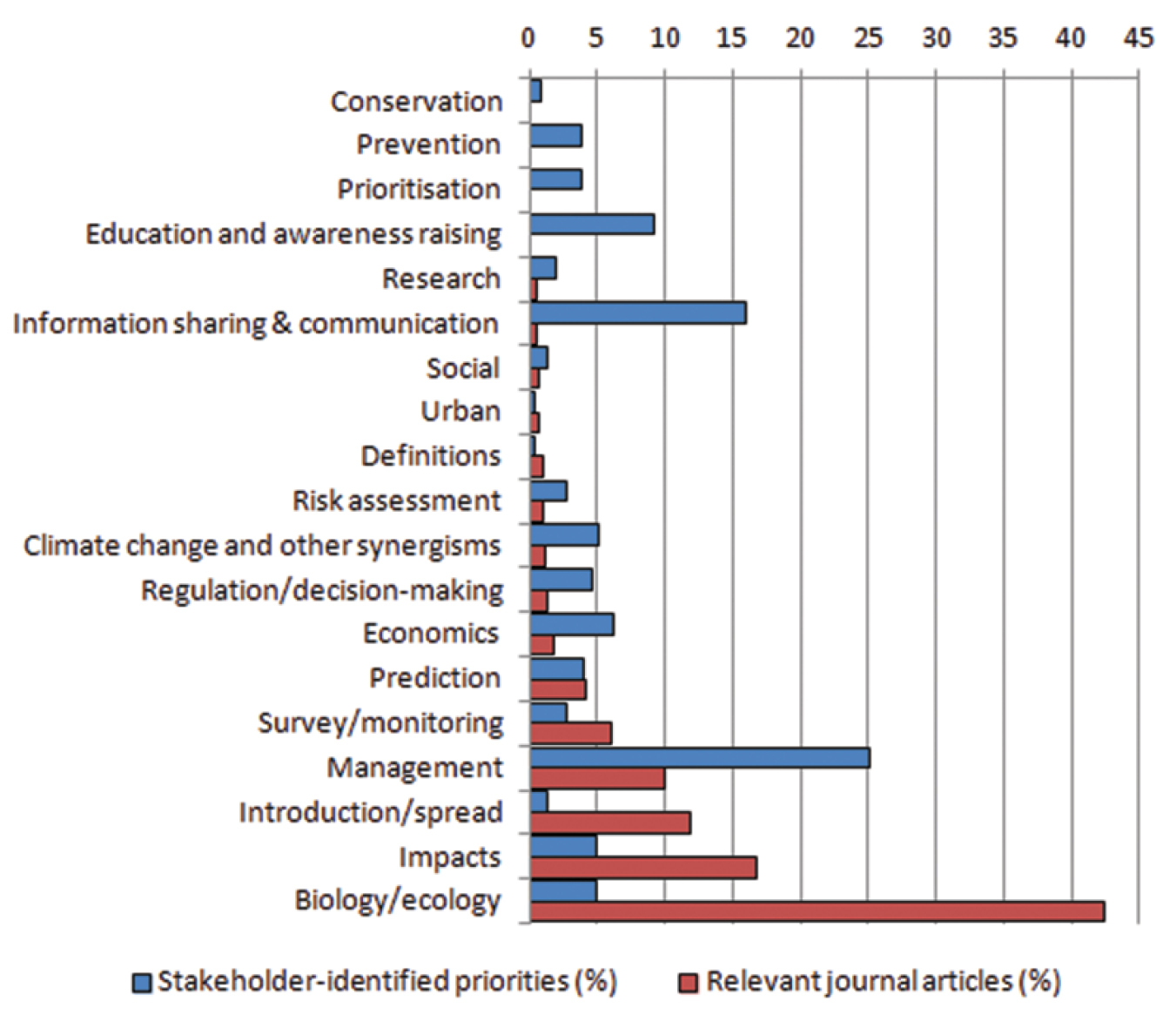

Nineteen broad priority categories or topics were identified (Figure 1). A quarter of all of the priorities identified by stakeholders (25.2%) related to the management of biological invasions. A further 16% related to information sharing, communication and collaboration, 9.1% related to education and awareness raising, 6.2% to economics, 5.1% to climate change and 4.9% each to impacts of invasive species and to synergies with climate change and other threat drivers.

The relative proportions (%) of topics identified by stakeholders working with invasive species as priority areas for invasive species science and management compared to the topics of relevant journal articles published in eight journals over the same period (2009–2010).

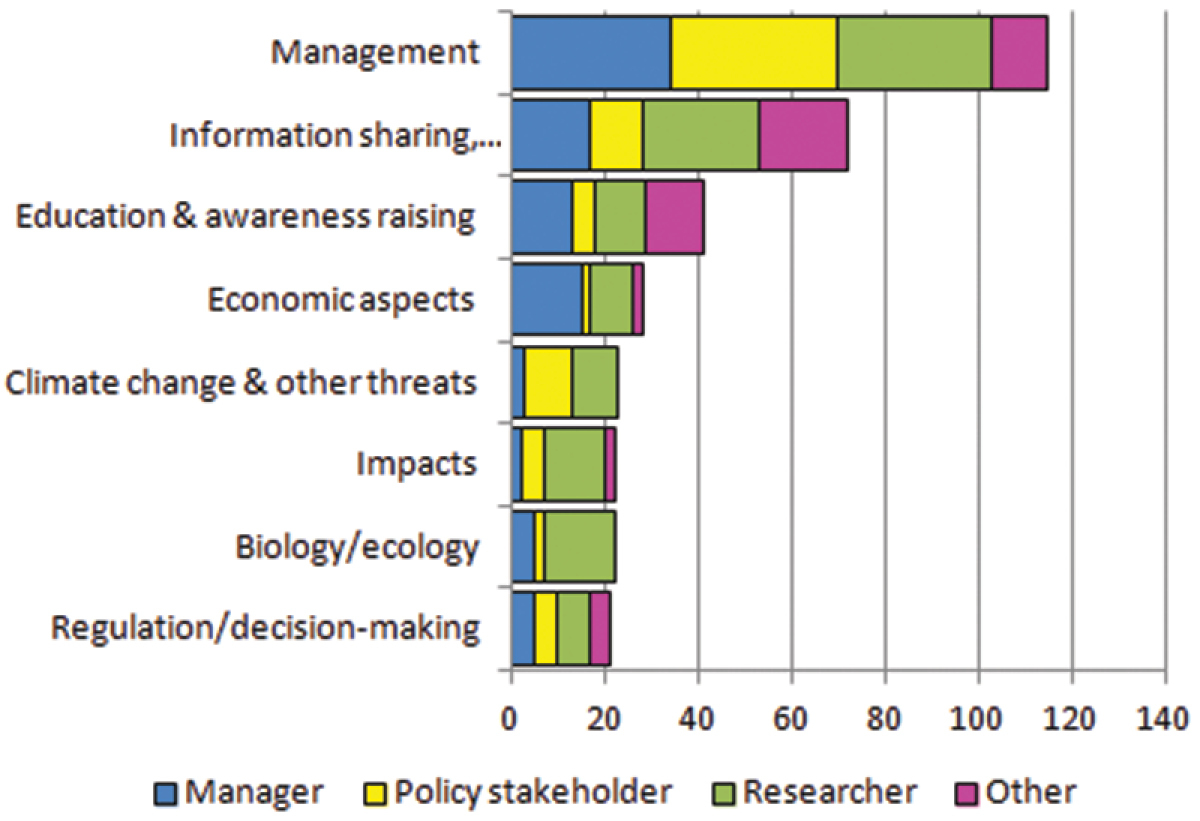

When compared across stakeholder groups, the two most frequently identified priorities were the same for stakeholders working in management, policy and research; these were the management of invasive species, followed by information sharing, communication and collaboration (Figure 2). Despite being the most frequently identified, these topics represented varying proportions of the overall priorities within different stakeholder categories, representing 31.2% and 15.9% of manager priorities, 38.3% and 11.7% of policy stakeholder priorities and only 18.6% and 14.1% of researcher priorities respectively (Table 2). The order and relative proportions of subsequent priorities varied between stakeholder groups. Researchers identified priorities within each of the 19 topic areas, managers within 16, policy stakeholders within 15, whilst the ‘other stakeholders’ category only identified priorities within 13 of the topic areas. The ‘other stakeholders’ group most frequently identified information sharing, communication and collaboration as a key priority (27.5%), followed by education and awareness raising and the management of invasive species (17.4% each).

The eight main priority areas for invasive species science and management (each proposed twenty or more times) based on 344 of the 449 priorities identified by 158 stakeholders working with invasive species during 2009–2010 and depicted as absolute values broken down by stakeholder group. Detailed legend: Data plotted represents 94 of the total priorities provided by the 38 practitioners; 76 provided by the 32 policy stakeholders; 123 provided by the 64 researchers; and 51 provided by the 24 other stakeholders.

Relative proportions (% to 1dp) of journal articles and stakeholder priorities (total and by individual stakeholder groups) addressing each of the 19 topics in invasive species science and management and collated during 2009–2010.

| Topic | Relevant journal articles (%) | Total % of stakeholder-identified priorities | Manager % | Policy stakeholder % | Researcher % | Other % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biology/ecology | 42.5 | 4.9 | 4.6 | 2.1 | 8.5 | 0 |

| Climate change and other synergisms | 1.1 | 5.1 | 2.8 | 10.6 | 5.6 | 0 |

| Conservation | 0 | 0.9 | 0 | 0 | 2.3 | 0 |

| Definitions | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 1.1 | 0 |

| Economics | 1.8 | 6.2 | 13.8 | 2.1 | 5.1 | 2.9 |

| Education and awareness raising | 0 | 9.1 | 11.9 | 5.3 | 6.2 | 17.4 |

| Impacts | 16.7 | 4.9 | 1.8 | 5.3 | 7.3 | 2.9 |

| Information sharing, communication and collaboration | 0.5 | 16.0 | 15.6 | 11.7 | 14.1 | 27.5 |

| Introduction/spread | 11.9 | 1.3 | 0 | 3.2 | 1.7 | 0 |

| Management | 10.0 | 25.2 | 31.2 | 38.3 | 18.6 | 17.4 |

| Prediction | 4.2 | 4.0 | 0.9 | 2.1 | 7.9 | 1.4 |

| Prevention | 0 | 3.8 | 1.8 | 3.2 | 2.8 | 10.1 |

| Prioritisation | 0 | 3.8 | 3.7 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 5.8 |

| Regulation/decision-making | 1.3 | 4.7 | 4.6 | 5.3 | 4.0 | 5.8 |

| Research | 0.5 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 2.8 | 1.4 |

| Risk assessment | 1.0 | 2.7 | 1.8 | 4.3 | 2.8 | 1.4 |

| Social | 0.6 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 2.1 | 1.1 | 1.4 |

| Survey/monitoring | 6.1 | 2.7 | 1.8 | 0 | 4.0 | 4.3 |

| Urban | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.6 | 0 |

789 articles of broad relevance to invasive species were identified from the eight journals during the two year period. Biological Invasions unsurprisingly published the highest number of articles deemed relevant to invasion biology as the only specialist journal included in the sample (545 articles). Diversity and Distributions published the second highest number (82), followed by Weed Research (75) and The Journal of Applied Ecology (48). Ecological Economics contained 12 articles, Journal of Environmental Management contained 11, Trends in Ecology and Evolution contained nine, and Conservation Evidence contained seven relevant articles. The majority of articles retrieved were original research articles.

Most journal articles related to the ecology or biology of invasive species (42.5%), the impacts of biological invasions (16.7%), or modes of introduction and spread (11.9%). The 79 management articles identified represented 10% of the sample. Approximately 6% of papers related to surveying or monitoring and 4.2% to prediction for invasive species. All other topics were the focus of less than 2% of articles in the sample.

The greatest proportion of research papers related broadly to the biology and ecology of invasive species, whereas the greatest proportion of stakeholder priorities related to management (Figure 2). The odds ratio tests indicated that the proportion of topics identified as priorities by stakeholders were statistically different from the topics covered by journal articles for 14 out of 19 topics (p ≤ 0.05; Table 3), indicating a mismatch. Education and awareness raising, prevention, prioritisation, information sharing and communication and conservation had the largest effect sizes, suggesting that they were under-represented in the literature when compared to the stakeholder priorities. Conservation, definitions, predictions, social issues and urban invasives were not significantly different with the 95% confidence interval crossing 1, suggesting that coverage of these topics by journals is roughly proportional to their identification as priorities; however, these topics represented only small values in both categories and so the odds ratios were likely to be closer to one.

Odds ratios with calculated 95% confidence intervals, z statistics and p values comparing the differences between the relative frequencies of stakeholder-identified priorities for invasive species science and management and the topics of journal articles published during the same period (2009–2010).

| Topic | a) Number of times priority identified by stakeholders | b) Total number of other priorities | c) Number of relevant journal articles | d) Total number of other journal articles | Odds Ratio (a/b) / (c/d) to 2 dp | 95% CI | z statistic | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate change and other synergistic threats | 23 | 426 | 9 | 780 | 4.68 | 2.15 to 10.20 | 3.88 | P = 0.0001 |

| Conservation | 4 | 445 | 0 | 789 | 15.95 | 0.86 to 296.94 | 1.86 | P = 0.0634 |

| Definitions | 2 | 447 | 8 | 781 | 0.44 | 0.09 to 2.06 | 1.05 | P = 0.2961 |

| Biology/ecology | 22 | 427 | 335 | 454 | 0.07 | 0.05 to 0.11 | 11.56 | P <0.0001 |

| Economics | 28 | 421 | 14 | 775 | 3.68 | 1.92 to 7.07 | 3.92 | P = 0.0001 |

| Education and awareness raising | 41 | 408 | 0 | 789 | 160.41 | 9.84 to 2614.46 | 3.57 | P = 0.0004 |

| Impacts | 22 | 427 | 132 | 657 | 0.26 | 0.16 to 0.41 | 5.71 | P < 0.0001 |

| Information sharing, communication and collaboration | 72 | 377 | 4 | 785 | 37.48 | 13.59 to 103.35 | 7.00 | P < 0.0001 |

| Introduction/spread | 6 | 443 | 94 | 695 | 0.10 | 0.04 to 0.23 | 5.41 | P < 0.0001 |

| Management | 113 | 336 | 79 | 710 | 3.02 | 2.20 to 4.14 | 6.87 | P < 0.0001 |

| Prediction | 18 | 431 | 33 | 756 | 0.96 | 0.53 to 1.72 | 0.15 | P = 0.8825 |

| Prevention | 17 | 432 | 0 | 789 | 63.89 | 3.83 to 1065.06 | 2.90 | P = 0.0038 |

| Prioritisation | 17 | 432 | 0 | 789 | 63.89 | 3.83 to 1065.06 | 2.90 | P = 0.0038 |

| Regulation/decision-making | 21 | 428 | 10 | 779 | 3.82 | 1.78 to 8.19 | 3.45 | P = 0.0006 |

| Research | 9 | 440 | 4 | 785 | 4.01 | 1.23 to 13.11 | 2.30 | P = 0.0214 |

| Risk assessment | 12 | 437 | 8 | 781 | 2.68 | 1.09 to 6.61 | 2.14 | P = 0.0322 |

| Social | 6 | 443 | 5 | 784 | 2.12 | 0.64 to 7.00 | 1.24 | P = 0.2158 |

| Survey/monitoring | 12 | 437 | 48 | 741 | 0.42 | 0.22 to 0.81 | 2.61 | P = 0.0090 |

| Urban | 2 | 447 | 6 | 783 | 0.58 | 0.12 to 2.91 | 0.66 | P = 0.5110 |

Our results showed an apparent mismatch between the topics relating to invasive species reported in journal articles and the priority areas for science and management identified by stakeholders. This disparity, and in particular the lack of focus on management in the scientific literature, may be creating the perception that there is a gap between invasive species research and practice, supporting criticisms that research is not geared towards delivering practical solutions (e.g.

Firstly, individual journal articles appeared to address multiple priority areas but were focused on specific species, sites or geographic regions, such as the introduction, spread and impacts of an individual species, whereas the priority areas identified by stakeholders in our sample were focused on defined topics such as ‘management techniques’ or ‘surveying and monitoring’. This difference is likely to be due, at least in part, to the practicalities of undertaking field or laboratory research, necessitating greater focus and control.

Secondly, there is a clear justification for the focus on basic research on the ecology and population biology of invasive species. Fundamental research relating to both biology and management practices, as well as more advanced applied research such as modelling, are necessary to tackle the problems associated with invasive species and deliver practical solutions in the field (

Thirdly, many journals focus on publishing articles that demonstrate novelty and broad interest, meaning that localised management studies may be seen as parochial and be rejected. Management actions are usually undertaken by non-research scientists and so the imperative to publish in academic journals is likely to be less, whilst negative results observed in the field may be difficult to get published but can have important implications for management (

Finally, there may be a potential lag time between the identification of a priority and the reporting of research outcomes due to the time taken to mobilise funding and undertake the research. A comparison of stakeholder priorities collated several years prior to research outputs may provide a better reflection of the responsive nature of research.

Biological invasions are by their nature multidisciplinary, and a wide range of subjects need to contribute to their successful management (

Despite differences in the cultures and activities of different stakeholder groups, the two most frequently identified priority areas were the same for researchers, practitioners and policy stakeholders. This suggests that these areas, effective management and enhanced information sharing, communication and collaboration, require urgent attention. Although many of the stakeholder-identified priorities were addressed by research papers, important topics like education and awareness raising or prioritisation do not appear to be receiving sufficient coverage. Whilst these may not be the predominant tasks for scientists, an increasing focus on interdisciplinary projects like the Working for Water programme in South Africa may help to address the lack of coverage these topics currently receive. Although the largest proportion of respondents were researchers, their priorities still did not match the topics covered by journal articles, although they appear least different. However, they were the only stakeholders to identify as priorities some of the topics that were not significantly different from the topics of journal articles (i.e. conservation and definitions).

Although the management of invasive species was a key priority identified by stakeholders, we identified a lack of papers in the literature focused on the management of biological invasions, with most of those identified studying the impacts of invasive species control or eradication rather than its effectiveness. Other papers addressed management indirectly, for example by discussing the potential implications of a species’ ecology on the effectiveness of management. The strong focus towards biology and ecology identified within the journal articles is likely to reflect the interests of the journals covered by this exercise; it is worth noting that the ecological journals contributed almost 87% of the total studies included in the analysis, and so despite efforts to include data from other journals to reduce the bias towards ecological studies, the greater volume of papers produced in these journals may also help to explain the focus towards ecological studies in the results. It may be interesting to repeat this exercise once more of the journals focused specifically on the field of biological invasions have had time to establish and mature.

Invasion biology as a discipline may need to find alternative mechanisms for collecting management information. There are many mechanisms available which can help, including publicly accessible newsletters and databases such as the Conservation Evidence database and practitioner journal (www.conservationevidence.com), which includes case studies of invasive species management projects.

Of course, it is important to note that scientific information derived from research forms only one component of environmental management decisions. Previous research suggests that scientists are not keen to make decisive statements, preferring instead to articulate uncertainty and recommend other sources of information, whilst managers often have to make rapid decisions before all scientific information has been evaluated (

Invasion biology, and ecology as a whole, may benefit from an independent organisation that draws scientific data together with other forms of relevant information to provide guidance on best practice, which could identify and steer funding towards the most pressing and topical questions. This would prove challenging as cohesion between stakeholders would be necessary, and this would depend on adopting a realistic and practical scale at which to operate. There is still a clear need for more basic research in invasion biology to provide the information necessary to elaborate more applied recommendations. Regardless of whether the priorities identified by stakeholders are addressed by research activities, there is a need to evaluate and share best practice. Traditional ecologically focused journals may not always provide the best forum for this, but as a community we need to ensure that information is being shared to enhance the integrated management of biological invasions.

Similarities in the priorities most frequently identified by different stakeholder groups suggest that there are broad topics that urgently need addressing, particularly in relation to the lack of research directly relevant to management or to sociological aspects of invasion biology such as education and awareness-raising. These may need to be addressed through research or through the evaluation and sharing of current experience to inform future practice. Whilst there are many topics still to be explored fully in invasion biology (e.g.

As a community, we need to ensure that any research with practical applications to invasive species management addresses the needs of the stakeholders that ultimately stand to benefit from our science, either directly by undertaking targeted research with practical applications, or by ensuring that ‘pure’ biological and ecological research is translated or synthesised, either by researchers or by people trained for this purpose, so that the implications are better understood. By ensuring that the potential application of research is clearly expressed, and by finding ways to bridge the difference between research papers and stakeholder needs, efforts to control invasive species and the theoretical science of invasion biology will both be strengthened.

We particularly thank all of the individuals that provided us with their priorities for science and management. We also thank the British Ecological Society Invasive Species Group, the GB Non Native Species Secretariat, the Society for Conservation Biology European Section and the other individuals and organisations that kindly supported our workshops and questionnaires. We also thank Peter Mills and Jane Hill for feedback, and Ingolf Kühn and two anonymous referees whose comments helped greatly improve an earlier version of this manuscript.

Stakeholder priorities. (doi: 10.3897/neobiota.19.4897.app1) File format: Micrisoft Comma Separated Value File (csv).

Explanation note: File containing stakeholder-identified priorities for invasive species science and management along with source from which they were obtained, stakeholder category (policy maker, practitioner, researcher or other) and the classification of the priority used for analysis.

Journal article classifications (doi: 10.3897/neobiota.19.4897.app2) File format: Comma Separated Value File (csv).

Explanation note: File containing details of journal articles relevant to biological invasions included in the analysis, source journals and the main area of classification used for analysis.