Research Article |

|

Corresponding author: Elizabete Marchante ( emarchante@uc.pt ) Academic editor: John Ross Wilson

© 2022 Veronica Price-Jones, Peter M. J. Brown, Tim Adriaens, Elena Tricarico, Rachel A. Farrow, Ana Cristina Cardoso, Eugenio Gervasini, Quentin Groom, Lien Reyserhove, Sven Schade, Chrisa Tsinaraki, Elizabete Marchante.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Citation:

Price-Jones V, Brown PMJ, Adriaens T, Tricarico E, Farrow RA, Cardoso AC, Gervasini E, Groom Q, Reyserhove L, Schade S, Tsinaraki C, Marchante E (2022) Eyes on the aliens: citizen science contributes to research, policy and management of biological invasions in Europe. NeoBiota 78: 1-24. https://doi.org/10.3897/neobiota.78.81476

|

Abstract

Invasive alien species (IAS) are a key driver of global biodiversity loss. Reducing their spread and impact is a target of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG target 15.8) and of the EU IAS Regulation 1143/2014. The use of citizen science offers various benefits to alien species’ decision-making and to society, since public participation in research and management boosts awareness, engagement and scientific literacy and can reduce conflict in IAS management. We report the results of a survey on alien species citizen science initiatives within the framework of the European Cooperation in Science and Technology (COST) Action Alien-CSI. We gathered metadata on 103 initiatives across 41 countries, excluding general biodiversity reporting portals, spanning from 2005 to 2020, offering the most comprehensive account of alien species citizen science initiatives on the continent to date. We retrieved information on project scope, policy relevance, engagement methods, data capture, data quality and data management, methods and technologies applied and performance indicators such as the number of records coming from projects, the numbers of participants and publications. The 103 initiatives were unevenly distributed geographically, with countries with a tradition of citizen science showing more active projects. The majority of projects were contributory and were run at a national scale, targeting the general public, alien plants and insects, and terrestrial ecosystems. These factors of project scope were consistent between geographic regions. Most projects focused on collecting species presence or abundance data, aiming to map presence and spread. As 75% of the initiatives specifically collected data on IAS of Union Concern, citizen science in Europe is of policy relevance. Despite this, only half of the projects indicated sustainable funding. Nearly all projects had validation in place to verify species identifications. Strikingly, only about one third of the projects shared their data with open data repositories such as the Global Biodiversity Information Facility or the European Alien Species Information Network. Moreover, many did not adhere to the principles of FAIR data management. Finally, certain factors of engagement, feedback and support, had significant impacts on project performance, with the provision of a map with sightings being especially beneficial. Based on this dataset, we offer suggestions to strengthen the network of IAS citizen science projects and to foster knowledge exchange among citizens, scientists, managers, policy-makers, local authorities, and other stakeholders.

Keywords

biological recording, community science, crowdsourcing, non-native species, public engagement, survey

Introduction

The history of citizen science, broadly defined as the practice of involving members of the public in scientific research, can be traced back centuries (

One area in which citizen science has seen an increase in contributions is the domain of alien species science and policy (

The data gathered through IAS-focussed projects are eminently actionable, as they hold potential for use in early warning and rapid response, control programmes at various spatial scales, and policy implementation. Citizen science is especially valuable in an IAS context since tackling the spread of these species necessitates upscaled recording both temporally and geographically, improved understanding of the IAS problem, and increased awareness at all levels of society, objectives for which citizen science is well suited (

In addition to developing a database of European alien species citizen science projects, we were interested in determining if there were geographic differences in three parameters of project scope (target taxon, target audience and environment type), as an indicator for international cooperation. We further evaluated the performance of projects considering their numbers of participants, number of alien species records they yielded and the publications derived from them, in order to understand how various engagement, feedback and support parameters contributed to project performance.

Materials and methods

Data collection

This survey was developed within the scope of the European Cooperation in Science & Technology (COST) Action CA17122 – “Increasing understanding of alien species through citizen science (Alien-CSI)”, which includes participants from all EU Member States and a few neighboring countries. This COST Action sets out six research coordination objectives, to be first approached through a European wide analysis of existing IAS citizen science initiatives (

The first version of the survey was tested, revised and validated in a COST Action workshop in Akrotiri, Cyprus, 25 – 28 February 2019. Representatives from 25 countries in the COST Action attended. The survey (

Survey questions and attribute values were developed using JRC metadata standards for citizen science projects (

Preprocessing

Only projects that simultaneously fulfilled the following criteria were included in the analyses: 1) a clearly citizen science-focused project; 2) alien species included in the main scope; and 3) projects developed in Europe (even if not exclusively). As such, national biodiversity networks and portals collecting data on all species were only considered if they had a clear alien species focus. Projects needed to have specific forms of public engagement related to alien species, so projects solely devoted to improving IAS policies but without a typical citizen science component (e.g., data collection using target groups, interaction with volunteers) were not considered. However, projects where data gathering was less relevant, but which had clear educational and outreach goals on IAS, were included.

Due to response rates below 100% for particular questions and the prevalence of responses “Unknown” or “Not applicable”, the number of projects that provided a definite response was determined and used for calculations of percentages for each question.

Statistical analysis

Exploratory analysis of project parameters

Of the nine survey sections, six asked for information about project parameters, or characteristics. These sections are: General characterisation of the project, Information on project scope, Policy-related information, Information on engagement, Information on feedback and support, and Data quality and data management strategies. To explore the parameters of all surveyed projects, the frequency of each multiple choice or written answer was determined for each question within the above sections. Additionally, we were interested in determining if an association existed between target audience and target taxonomic group, or between target audience and target environment. Fisher’s exact tests were conducted with a significance level of 0.05 to test for these associations.

Geographic differences in project scope

In these series of analyses, we were interested in whether there were geographic differences in the distribution of projects, and whether project scope had a geographic component. For this, we divided Europe into five regions: Northern Europe, Eastern Europe, Southern Europe, Western Europe, and the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland (the UK and ROI). The UK is considered as a separate region with the ROI due to an extensive history with citizen science (

Impact of engagement, feedback and support on project performance

To test whether parameters which related to engagement, feedback and support had an effect on project performance, we selected 11 explanatory variables (project duration, four variables related to engagement, and six variables related to feedback/support) and defined three project performance indicators: the number of participants taking part in the project, the number of species records (observations) gathered by the project and the number of publications related to the project reported by the respondent (Table

| Explanatory variables | Response variables |

|---|---|

| Project duration | Number of participants |

| Project design (collaborative/contributory; engagement factor) | Number of records |

| Use of social media (engagement factor) | Number of publications |

| Level of skill/knowledge required (none/low/advanced; engagement factor) | |

| Expected contribution frequency (one-off/irregular/regular; engagement factor) | |

| Provision of guidelines (feedback and support factor) | |

| Provision of training (feedback and support factor) | |

| Provision of sightings map (feedback and support factor) | |

| Provision of active informing (feedback and support factor) | |

| Provision of feedback (feedback and support factor) | |

| Provision of support (feedback and support factor) | |

Results

Exploratory analysis of selected project parameters

General characterisation of the project

In total, 129 projects/initiatives completed data for the survey and, of these, 103 fitted the criteria for inclusion and were considered for analysis. Of the 26 that were excluded, 17 were not alien species-focused, seven had no specific forms of public engagement on alien species and two were duplicate entries.

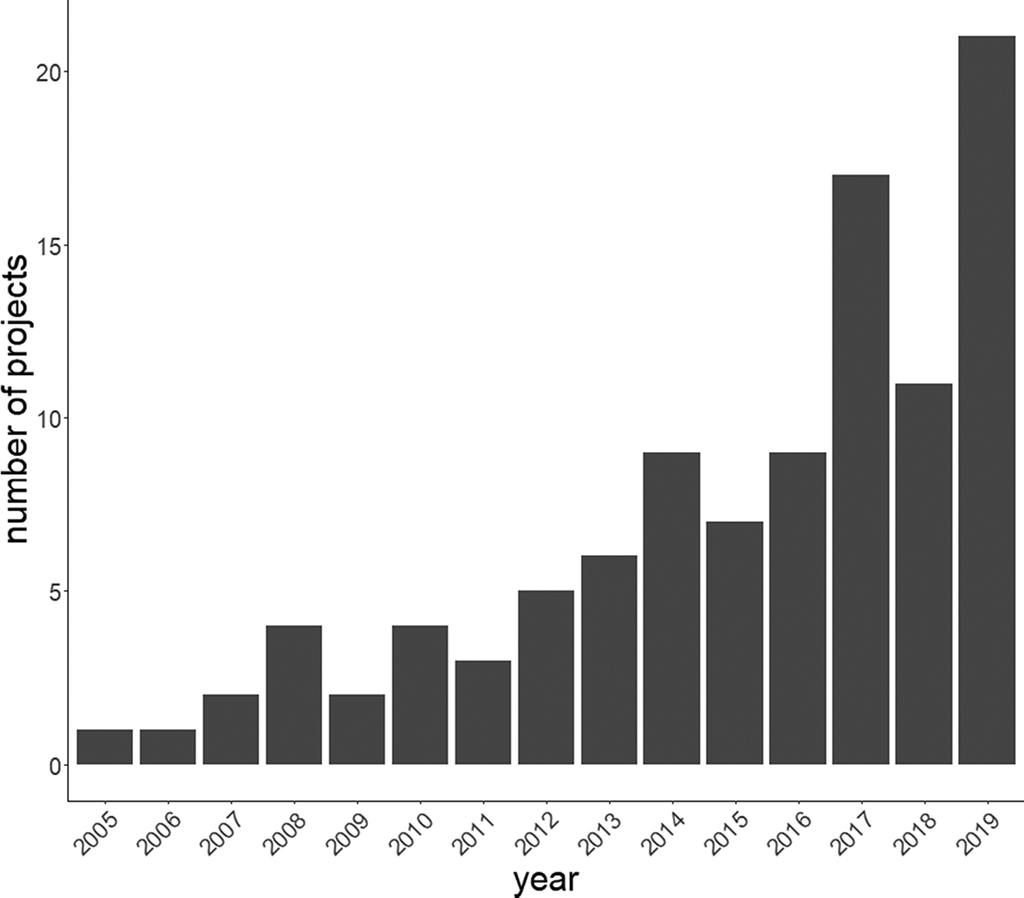

The number of new projects has increased over the past fifteen years with the oldest project recorded beginning in 2005 (

Number of new citizen science projects per year on alien species in Europe according to responses to the survey.

The type of organisation responsible for the projects varied between governmental (29%, 30/103) and non-governmental organisations (22%, 23/103), universities (28%, 29/103), public research organisations (22%, 23/103), and private companies, non-profit organisations and individual persons (12%, 12/103). Most projects were fully (54%, 56/103) or partially (19%, 20/103) funded, but 26% (27/103) reported having no funding. Governments were the largest source of funding, although only 36% of projects (28/78) report governments as being their sole source of funding. Otherwise, funding was provided by public entities, the EU LIFE program, NGOs or private sources, or a combination of the above.

Project scope

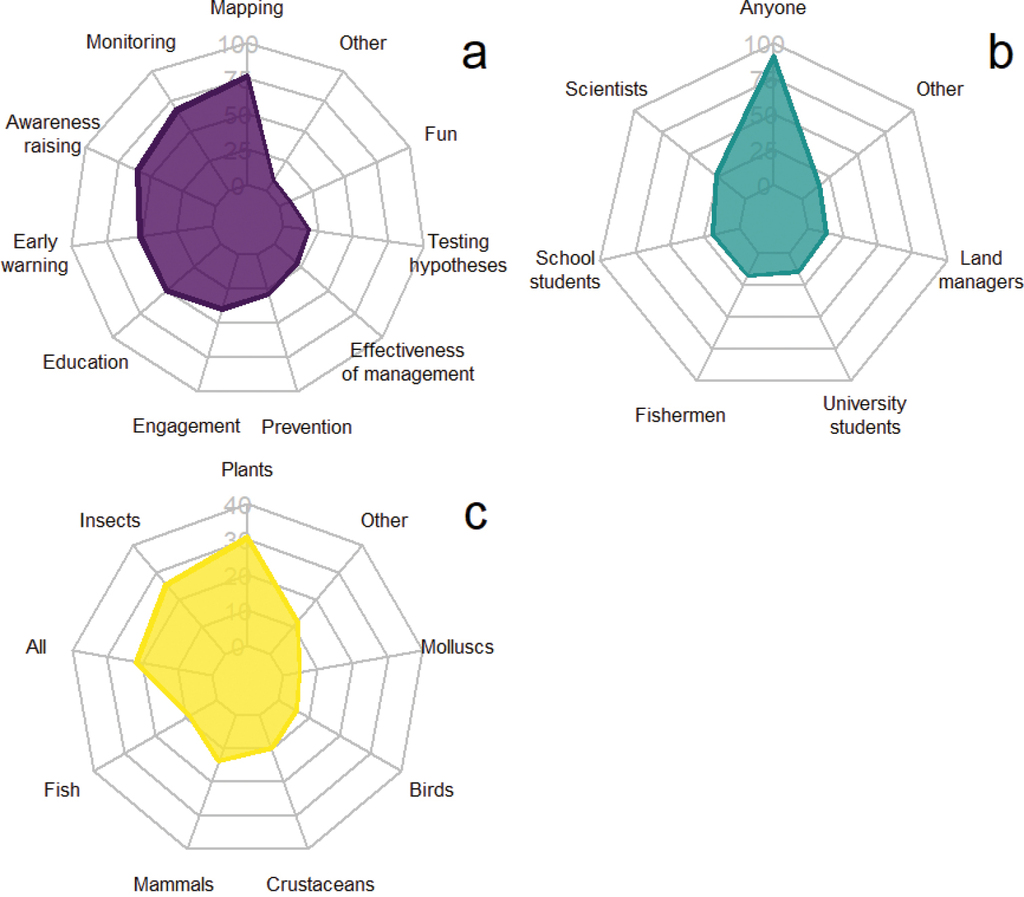

Plants were the most common target taxonomic group (30%, 31/103; Fig.

Percentage (indicated by numbers on radar plots) of projects that gave selected responses to project scope questions: a target taxon b target audience, and c stated project aim.

84% of projects (87/103) focused solely on alien species and 9% (9/103) focused partially on alien species; 7% (7/103) responded that alien species were not the main focus, yet alien species data were collected and received some emphasis. Most projects had multiple aims, the most common being mapping of alien species distribution (Fig.

Policy-related information

75% of projects (59/79) claimed to have policy relevance, with 79% (77/97) including species on the list of IAS of Union concern (EU Regulation 1143/2014), whether exclusively or partially.

Information on engagement

In terms of project design, 39% of projects (41/97) were categorised as collaborative (citizen scientist input was possible in project design) and 53% (56/97) as contributory (projects were designed only by scientists). The top three ways to engage citizens with the projects were through websites (83%, 83/99), social media (64%, 64/99) and live training (41%, 41/99). Newsletters, school engagement, exhibitions, bioblitzes and gaming were also common methods, each used by six or more projects. Of the projects that used social media and stated the platform, Facebook was the most popular platform, used by 65% of projects (63/96), but Twitter, Instagram and YouTube were also used. Almost 95% of projects (94/99) responded that participants needed “None” or “Limited” prior skills or knowledge to participate.

Information on feedback and support

The number of projects that provided species identification materials, guidelines, training, sighting maps, active informing, feedback and support is shown in Table

Responses to survey questions concerning various feedback and support factors.

| Factor | Percentage of projects | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Partial (if applicable) | |

| Provision of species identification materials | 76% (74/98) | 7% (7/98) | 17% (17/98) |

| Provision of guidelines | 87% (85/98) | 13% (13/98) | – |

| Provision of training | 67% (64/95) | 33% (31/95) | – |

| Provision of sightings map | 86% (78/91) | 14% (13/91) | – |

| Provision of active informing | 69% (64/93) | 7% (7/93) | 24% (22/93) |

| Provision of feedback | 89% (71/80) | 11% (9/80) | – |

| Provision of support | 93% (85/91) | 7% (6/91) | – |

Data quality and data management

The large majority (86%, 89/103) of the projects surveyed had validation systems in place, and 6% (6/103) had partially implemented validation systems. An additional 6% (6/103) of respondents indicated that the validation system was unknown to them and only 2% (2/103) responded they did not have validation in place. Within the subset of projects implementing validation procedures, expert validation was most commonly used, by at least 93% (93/100) of projects. Validation was either performed solely by experts (77%, 77/100), aided by automated systems (3%, 3/100) or peer validation (9%, 9/100), or a combined approach was used (3%, 3/100). Peer validation and automated validation without expert validation were only used by a minority of projects (2%, 2/100).

For data storage, projects used national repositories (38%, 34/89), hard drives (34%, 30/89), GBIF (30%, 27/89) and institutional repositories (23%, 21/89). 58 projects offered participants direct access to their own data. Excel (65%, 44/68) was the most common data form and Darwin Core (50%, 18/36) the most popular data standard. The license Creative Common Attribution (CC BY; 57%, 16/29) was the most common, followed by CC0 licence waiver (10%, 3/29) and Creative Commons Non-Commercial licence (7%, 2/29). Finally, most projects did not draft a data management plan (73%, 40/55).

Project performance

The usage of applications, number of participants, number of records and number of publications all show a distribution of responses that peaked in lower numbers and fell off quickly at higher numbers (Fig.

Geographic differences in project scope

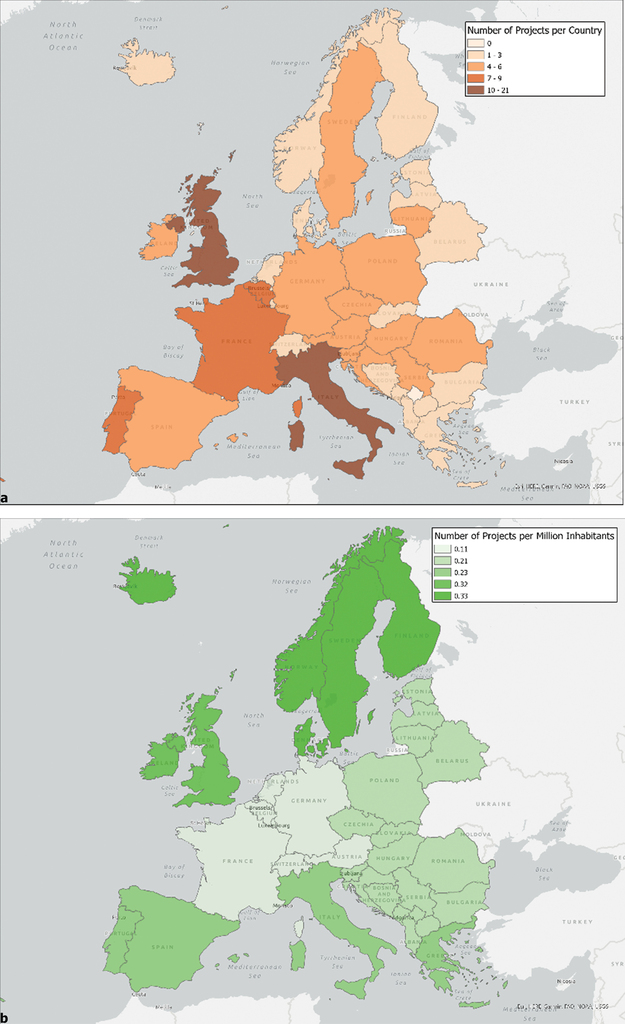

According to responses to our survey, the UK had more alien species citizen science projects (21) than any other country, followed by Italy (13), Portugal (9) and France (9) (Fig.

Engagement methods and performance

Project duration had a significant, positive impact on the three performance indicators tested, i.e., number of participants (z = 2.78, df = 1, p = 0.0054), publications (z = 3.38, df = 1, p = 0.00073) and records (z = 3.01, df = 1, p = 0.0026). Projects that provided a map also outperformed projects that did not in number of participants (z = 2.13, df = 2, p = 0.033), publications (z = 2.77, df = 2, p = 0.0056) and records (z = 2.84, df = 2, p = 0.0045).

Provision of training was positively related to the number of publications (z = 2.85, df = 1, p = 0.044), as was use of social media (z = 2.35, df = 1, p = 0.019) and provision of guidelines (z = 2.01, df = 1, p = 0.045). Projects that required advanced prior knowledge resulted in more publications than projects that required limited (z = -2.80, df = 2, p = 0.0052) or no (z = -2.74, df = 2, p = 0.0061) prior knowledge. The same result was seen in terms of number of records, with projects that required advanced prior knowledge performing better than projects that required limited (z = -2.47, df = 2, p = 0.014) or no (z = -2.02, df = 2, p = 0.043) prior knowledge.

Provision of feedback positively impacted the number of publications (z = 2.01, df = 1, p = 0.044) but negatively impacted the number of records (z = -2.01, df = 1, p = 0.044). Provision of support negatively impacted the number of publications (z = -2.59, f = 1, p = 0.0096).

Discussion

Project scope and regional variation

The dominance of national projects in our results is consistent with that observed for other research on management of biological invasions (

Most projects target the general public, which is logical given our inclusion criteria. This strategy aligns with the philosophy of informing (

The prevalence of projects in the terrestrial environment similarly reflects convenience for the public, as reported for other citizen science projects (

The most common aim is mapping of alien species, and participants are often asked to submit species presence and/or abundance data. Species presence is easy to observe, report and validate (

The region with the most recorded projects is the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland, reflecting a long history of citizen science in ecology (

Data quality and management

Studies evaluating data quality and management in citizen science projects sometimes have contradictory conclusions (

Data generated by citizen science are often referred to as dark data: unreproducible, becoming more valuable over time, and at high risk of being lost (

Opening alien species data is important to unlock their full potential for science, policy and management (

Optimisation of engagement

We anticipated that higher levels of feedback, support and engagement would improve performance, e.g., the number of participants, records and publications, through the generation of commitment and empowerment. As expected, provision of maps, training and guidelines related positively to one or more of the performance indicators. Unexpectedly, provision of feedback related positively to the number of publications, and negatively to the number of records; provision of support also negatively related to the number of publications. While citizen scientists often claim that receiving feedback is important to their continued participation (

Only 39% of the projects were designed collaboratively, thus in most cases citizens were contributing in a predetermined way (usually data collection). Even so, a priori fewer projects were expected to be collaborative (e.g.,

Surveyed projects mostly required low levels of time commitment for learning and participation, possibly recognising that most citizen scientists are amateur observers (

Although it depends on project goals, besides engaging participants, projects often encourage continued participation (

Finally, the majority of projects used an internet-based engagement method, such as a website or social media, reflecting the ubiquity of these technologies in Europe (

Applications and recommendations

Several lessons can be drawn from the results of our survey. First, sustainability of projects is key to their performance in terms of the number of records they gather, participants they involve and publications derived from them. Second, many citizen science projects apparently have not yet opened their data. Open data publication maximises the use of the data in policy processes, such as their use by EASIN in the implementation of the EU IAS Regulation (

One partial solution to openness and data management issues might be the drafting of DMPs, which are missing in many projects, despite these facilitating better storage, maintenance, and use of data. Although small projects may struggle to create their own, they may take advantage of existing plans, and strategies can be designed to make data openly accessible, for example on the platform GBIF. Few respondents provided information about their scientific outputs, and there is often no information on project web pages about where they publish their datasets.

To further improve outreach and onboarding of new citizen scientists, and sustained participation, our results suggest that the provision of maps with sightings and the provision of training are important. Future work could also be undertaken to compare the performance of different validation procedures and provide recommendations to new projects to improve data quality (

Our results show an increasing number of new alien species citizen science projects in the last few years that contribute to IAS mapping and policy implementation, but some regions still hold untapped potential for new citizen science initiatives related to alien species. Existing projects may be made accessible to new audiences through language translation or simplification, and through tailoring of aims and species lists to geographic regions (e.g., Invasive Alien Species in Europe application;

The UN’s SDGs provide an excellent model for how citizen science can be relevant to setting and achieving goals at a global level. Although SDGs were not initially developed with citizen science in mind, data gathered through citizen science can be used directly for feeding SDG indicators (

Conclusions

The number of citizen science projects dedicated to alien species has been on the rise in Europe in the last decade, yet some regions in Europe still hold untapped potential for new initiatives. Citizen science initiatives often yield data on policy-relevant species, including species of the list of IAS of Union concern, and the data generated by these projects are used for science and management. Despite this, many projects face sustainability problems and only a minority of the data finds its way to open data repositories. Future work could explore the added value of specific alien species projects as compared to general citizen science biodiversity reporting portals, as well as the actual relevance of citizen science data in decision making on IAS. Also, the value of alien species citizen science in terms of increased engagement, learning outcomes and environmental awareness, needs to be further explored. To further foster active alien species citizen science across the continent, we suggest that strategies could be developed i) to support regions where alien species citizen science is currently only emerging and ii) to strengthen the links between projects and entities around the EU IAS Regulation. One way to do so is to provide networking opportunities where projects can exchange experiences.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Action CA17122 Increasing understanding of alien species through citizen science (Alien-CSI), supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology www.cost.eu) through workshops and a short term scientific mission (ECOST-STSM-CA17122-42402). We thank Tim Woods (ECSA), and the Flemish Knowledge centre for Citizen Science (SCivil) for disseminating the survey through their networks. We are grateful to all the project coordinators for filling the survey on citizen science initiatives: Alex Richter-Boix, Andrew Salisbury, Anna Gazda, Anne Goggin, Antonina dos Santos, Antonios Geropoulos, Ariadna Just, Balázs Károlyi, Baudewijn Odé, Benoit Lagier, Bernardo Duarte, Christian Ries, Christophe Bornand, Colette O’Flynn, Conrad Altmann, Daniel Dörler, Dave Kilbey, Diemer Vercayie, Dinka Matosevic, Elsa Quillery, Esra Per, Esther Hughes, Ferenc Lakatos, Francesco Tiralongo, Fredrik Dahl, Gabor Pozsgai, Hanna Koivula, Helen Roy, Helene Hennig, Hélia Marchante, Henk Groenewoud, Hugo Renato Marques Garcia Calado, Inês Correia Rosa, Ioannis Giovos, Jan Marcin Weslawski, Jean-Louis Chapuis, Jirislav Skuhrovec, Jitka Svobodová, Jo Clark, João Encarnação, João Loureiro, John Wilkinson, Jessica Thevenot, Julie Bailey, Jurga Motiejūnaitė, Karel Chobot, Karel Schoonvaere, Karolina Bacela-Spychalska, Katharina Dehnen-Schmutz, Katharina Lapin, Katrin Schneider, Kelly Martinou, Ladislav Pekarik, Luciana Zedda, Luís González Rodríguez, Luís Reino, Maarten de Groot, Malin Strand, Marija Smederevac-Lalić, Marina Golivets, Markus Seppälä, Michael Pocock, Michelle Cleary, Milica Jaćimović, Milvana Arko-Pijevac, Mirela Uzelac, Mónica Moura, Negin Ebrahimi, Nicole Nöske, Niki Chartosia, Nir Stern, Noé Ferreira Rodriguez, Ofer Steinitz, Ondřej Zicha, Paolo Balistreri, Pavel Pipek, Pedro Anastácio, Periklis Kleitou, Philippe Jourde, Quentin Rome, Rafal Maciaszek, Rigers Bakiu, Rory Putman,Rosa Olivo del Amo, Rui Botelho, Rumen Tomov, Sándor Nagy, Sandro Bertolino, Sofie De Smedt, Sonja Desnica, Tamas Komives, Tarso Costa, Tatsiana Lipinskaya, Tom Evans, Toril L. Moen, Valeria Lencioni, Victor Zamfir. We thank Craig Hilborn for advice on the statistical analysis.

References

- Aceves-Bueno E, Adeleye AS, Feraud M, Huang Y, Tao M, Yang Y, Anderson SE (2017) The accuracy of citizen science data: A quantitative review. Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America 98(4): 278–290. https://doi.org/10.1002/bes2.1336

- Adriaens T, Sutton-Croft M, Owen K, Brosens D, van Valkenburg J, Kilbey D, Groom Q, Ehmig C, Thürkow F, Hende PV, Schneider K (2015) Trying to engage the crowd in recording invasive alien species in Europe: Experiences from two smartphone applications in northwest Europe. Management of Biological Invasions 6(2): 215–225. https://doi.org/10.3391/mbi.2015.6.2.12

- Adriaens T, Tricarico E, Reyserhove L, Cardoso AC, Lopez Canizares C, Mitton I, Schade S, Spinelli F, Tsiamis K (2021) Data-validation solutions for citizen science data on invasive alien species: Tailoring validation tools for the JRC app “Invasive Alien Species in Europe”, EUR 30857 EN. Publications Office of the European, Luxembourg, JRC126140.

- Anđelković AA, Lawson Handley L, Marchante E, Adriaens T, Brown PMJ, Tricarico E, Verbrugge LNH (2022) A review of volunteers’ motivations to monitor and control invasive alien species. NeoBiota 73: 153–175. https://doi.org/10.3897/neobiota.73.79636

- Balázs B, Mooney P, Nováková E, Bastin L, Arsanjani JJ (2021) Chapter 8: Data Quality in Citizen Science. In: Vohland K, Land-Zandstra A, Ceccaroni L, Lemmens R, Perelló J, Ponti M, Samson R, Wagenknecht K (Eds) The Science of Citizen Science: 139–158. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-58278-4

- Bilton DT, Mirol PM, Mascheretti S, Fredga K, Zima J, Searle JB (1998) Mediterranean Europe as an area of endemism for small mammals rather than a source for northwards postglacial colonization. Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences 265(1402): 1219–1226. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1998.0423

- Bishop IJ, Warner S, van Noordwijk TCGE, Nyoni FC, Loiselle S (2020) Citizen Science Monitoring for Sustainable Development Goal Indicator 6.3.2 in England and Zambia. Sustainability 12(24): 10271. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410271

- Blackburn TM, Pyšek P, Bacher S, Carlton JT, Duncan RP, Jarošík V, Wilson JR, Richardson DM (2011) A proposed unified framework for biological invasions. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 26(7): 333–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2011.03.023

- Bonney R (1996) Citizen science: A lab tradition. Living Bird 15: 7–15.

- Bonney R, Phillips TB, Ballard HL, Enck JW (2016) Can citizen science enhance public understanding of science? Public Understanding of Science 25(1): 2–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662515607406

- Brown PMJ, Roy HE, Rothery P, Roy DB, Ware RL, Majerus MEN (2008) Harmonia axyridis in Great Britain: Analysis of the spread and distribution of a non-native coccinellid. BioControl 53(1): 55–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10526-007-9124-y

- César de Sá N, Marchante H, Marchante E, Cabral JA, Honrado JP, Vicente JR, de Sá NC (2019) Can citizen science data guide the surveillance of invasive plants? A model-based test with Acacia trees in Portugal. Biological Invasions 21(6): 2127–2141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-019-01962-6

- Christensen R (2018) (Submitted in) Cumulative link models for ordinal regression with the R package ordinal. Journal of Statistical Software, 1–40.

- Costello MJ, Wieczorek J (2014) Best practice for biodiversity data management and publication. Biological Conservation 173: 68–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2013.10.018

- European Union (2014) Regulation (EU) No. 1143/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the prevention and management of the introduction and spread of invasive alien species. Official Journal of the European Union L 317, 4 November 2014, 35–55.

- Cox JG, Lima SL (2006) Naiveté and an aquatic-terrestrial dichotomy in the effects of introduced predators. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 21(12): 674–680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2006.07.011

- Crall AW, Newman GJ, Stohlgren TJ, Holfelder KA, Graham J, Waller DM (2011) Assessing citizen science data quality: An invasive species case study. Conservation Letters 4(6): 433–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-263X.2011.00196.x

- Crowston K, Prestopnik NR (2013) Motivation and Data Quality in a Citizen Science Game: A Design Science Evaluation. 46th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. IEEE, 450–459. https://doi.org/10.1109/HICSS.2013.413

- Devictor V, Whittaker RJ, Beltrame C (2010) Beyond scarcity: Citizen science programmes as useful tools for conservation biogeography. Diversity & Distributions 16(3): 354–362. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4642.2009.00615.x

- Dissanayake RB, Stevenson M, Allavena R, Henning J (2019) The value of long-term citizen science data for monitoring koala populations. Scientific Reports 9(1): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-46376-5

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Environment (2018) Citizen science for environmental policy: development of an EU-wide inventory and analysis of selected practices, Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2779/961304

- Fraisl D, Campbell J, See L, Wehn U, Wardlaw J, Gold M, Moorthy I, Arias R, Piera J, Oliver JL, Masó J, Penker M, Fritz S (2020) Mapping citizen science contributions to the UN sustainable development goals. Sustainability Science 15(6): 1735–1751. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-020-00833-7

- Fritz S, See L, Carlson T, Haklay M, Oliver JL, Fraisl D, Mondardini R, Brocklehurst M, Shanley LA, Schade S, Wehn U, Abrate T, Anstee J, Arnold S, Billot M, Campbell J, Espey J, Gold M, Hager G, He S, Hepburn L, Hsu A, Long D, Masó J, McCallum I, Muniafu M, Moorthy I, Obersteiner M, Parker AJ, Weisspflug M, West S (2019) Citizen science and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Nature Sustainability 2(10): 922–930. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0390-3

- Ganzevoort W, van den Born RJG, Halffman W, Turnhout S (2017) Sharing biodiversity data: Citizen scientists’ concerns and motivations. Biodiversity and Conservation 26(12): 2821–2837. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-017-1391-z

- Genovesi P, Carboneras C, Vilà M, Walton P (2015) EU adopts innovative legislation on invasive species: A step towards a global response to biological invasions? Biological Invasions 17(5): 1307–1311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-014-0817-8

- Geoghegan H, Dyke A, Pateman R, West S, Everett G (2016) Understanding motivations for citizen science. Final report on behalf of UKEOF, University of Reading, Stockholm Environment Institute (University of York) and University of the West of England. http://www.ukeof.org.uk/resources/citizen-science-resources/MotivationsforCSREPORTFI-NALMay2016.pdf

- Goodenough AE (2010) Are the ecological impacts of alien species misrepresented? A review of the “native good, alien bad” philosophy. Community Ecology 11(1): 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1556/ComEc.11.2010.1.3

- Groom Q, Desmet P, Vanderhoeven S, Adriaens T (2015) The importance of open data for invasive alien species research, policy and management. Management of Biological Invasions 6(2): 119–125. https://doi.org/10.3391/mbi.2015.6.2.02

- Groom Q, Weatherdon L, Geijzendorffer IR (2017a) Is citizen science an open science in the case of biodiversity observations? Journal of Applied Ecology 54(2): 612–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12767

- Groom Q, Adriaens T, Desmet P, Simpson A, Wever AD, Bazos I, Cardoso AC, Charles L, Christopoulou A, Gazda A, Helmisaari H, Hobern D, Josefsson M, Lucy F, Marisavljevic D, Oszako T, Pergl J, Petrovic-Obradovic O, Prévot C, Ravn HP, Richards G, Roques A, Roy HE, Rozenberg M-AA, Scalera R, Tricarico E, Trichkova T, Vercayie D, Zenetos A, Vanderhoeven S (2017b) Seven Recommendations to Make Your Invasive Alien Species Data More Useful. Frontiers in Applied Mathematics and Statistics 3: 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fams.2017.00013

- Groom Q, Strubbe D, Adriaens T, Davis AJS, Desmet P, Oldoni D, Reyserhove L, Roy HE, Vanderhoeven S (2019) Empowering Citizens to Inform Decision-Making as a Way Forward to Support Invasive Alien Species Policy. Citizen Science: Theory and Practice 4(1): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.5334/cstp.238

- Haklay M, Fraisl D, Tzovaras BG, Hecker S, Gold M, Hager G, Ceccaroni L, Kieslinger B, Wehn U, Woods S, Nold C, Balázs B, Mazzonetto M, Ruefenacht S, Shanley LA, Wagenknecht K, Motion A, Sforzi A, Riemenschneider D, Dorler D, Heigl F, Schaefer T, Lindner A, Weißpflug M, Mačiulienė M, Vohland K (2021) Contours of citizen science: A vignette study. Royal Society Open Science 8(8): 202108. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.202108

- Haubrock PJ, Turbelin AJ, Cuthbert RN, Novoa A, Taylor NG, Angulo E, Ballesteros-Mejia L, Bodey TW, Capinha C, Diagne C, Essl F, Golivets M, Kirichenko N, Kourantidou M, Leroy B, Renault D, Verbrugge L, Courchamp F (2021) Economic costs of invasive alien species across Europe. NeoBiota 67: 153–190. https://doi.org/10.3897/neobiota.67.58196

- Heigl F, Kieslinger B, Paul KT, Uhlik J, Dörler D (2019) Opinion: Toward an international definition of citizen science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 116(17): 8089–8092. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1903393116

- Howard L, van Rees CB, Dahlquist Z, Luikart G, Hand BK (2022) A review of invasive species reporting apps for citizen science and opportunities for innovation. NeoBiota 71: 165–188. https://doi.org/10.3897/neobiota.71.79597

- Hulme P, Roy D, Cunha T, Larsson T (2008) A pan-European inventory of alien species: rationale, implementation and implications for managing biological invasions. Handbook of Alien Species in Europe. Springer, Dordrecht, Netherlands, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-8280-1_1

- Hulme PE, Nentwig W, Pyšek P, Vilà M (2009) Common market, shared problems: Time for a coordinated response to biological invasions in Europe? NeoBiota 8: 3–19.

- Hyder K, Townhill B, Anderson LG, Delany J, Pinnegar JK (2015) Can citizen science contribute to the evidence-base that underpins marine policy? Marine Policy 59: 112–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2015.04.022

- IPBES (2019) Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. In: Díaz S, Settele J, Brondízio ES, Ngo HT, Guèze M, Agard J, Arneth A, Balvanera P, Brauman KA, Butchart SHM, Chan KMA, Garibaldi LA, Ichii K, Liu J, Subramanian SM, Midgley GF, Miloslavich P, Molnár Z, Obura D, Pfaff A, Polasky S, Purvis A, Razzaque J, Reyers B, Chowdhury RR, Shin YJ, Visseren-Hamakers IJ, Willis KJ, Zayas CN (Eds) IPBES secretariat, Bonn, Germany, 56 pp. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3553579

- Johnson BA, Mader AD, Dasgupta R, Kumar P (2020) Citizen science and invasive alien species: An analysis of citizen science initiatives using information and communications technology (ICT) to collect invasive alien species observations. Global Ecology and Conservation 21: e00812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2019.e00812

- Katsanevakis S, Bogucarskis K, Gatto F, Vandekerkhove J, Deriu I, Cardoso AC (2012) Building the European Alien Species Information Network (EASIN): A novel approach for the exploration of distributed alien species data. BioInvasions Records 1(4): 235–245. https://doi.org/10.3391/bir.2012.1.4.01

- Katsanevakis S, Genovesi P, Gaiji S, Hvid HN, Roy H, Nunes AL, Aguado FS, Bogucarskis K, Debusscher B, Deriu I, Harrower C, Josefsson M, Lucy F, Marchini A, Richards G, Trichkova T, Vanderhoeven S, Zenetos A, Cardoso AC (2013) Implementing the European policies for alien species – networking, science, and partnership in a complex environment. Management of Biological Invasions 4(1): 3–6. https://doi.org/10.3391/mbi.2013.4.1.02

- Katsanevakis S, Deriu I, D’Amico F, Nunes AL, Sanchez SP, Crocetta F, Arianoutsou M, Bazos I, Christopoulou A, Curto G, Delipetrou P, Kokkoris Y, Panov VE, Rabitsch W, Roques A, Scalera R, Shirley SM, Tricarico E, Vannini A, Zenetos A, Zervou S, Zikos A, Cardoso AC (2015) European Alien Species Information Network (EASIN): Supporting European policies and scientific research. Management of Biological Invasions 6(2): 147–157. https://doi.org/10.3391/mbi.2015.6.2.05

- Kemp S (2021) Digital 2021: Global Digital Overview. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2021-global-digital-overview

- Kumar A, Sinha A, Kanaujia A (2019) Using citizen science in assessing the distribution of Sarus Crane (Grus antigone antigone) in Uttar Pradesh, India. International Journal of Biodiversity and Conservation 11(2): 58–68. https://doi.org/10.5897/IJBC2018.1245

- Kus Veenvliet J, Veenvliet P, de Groot M, Kutnar L [Eds] (2019) A Field Guide to Invasive Alien Species in European Forests. Nova vas, Institute Symbiosis, so. e.; The Silva Slovenica Publishing Centre, Slovenian Forestry Institute, Ljubljana, 1–132.

- Malek R, Tattoni C, Ciolli M, Corradini S, Andreis D, Ibrahim A, Mazzoni V, Eriksson A, Anfora G (2018) Coupling Traditional Monitoring and Citizen Science to Disentangle the Invasion of Halyomorpha halys. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 7(5): 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi7050171

- Penner LA (2002) Dispositional and Organizational Influences on Sustained Volunteerism: An Interactionist Perspective. The Journal of Social Issues 58(3): 447–467. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-4560.00270

- Perrings C, Burgiel S, Lonsdale M, Mooney H, Williamson M (2010) International cooperation in the solution to trade-related invasive species risks. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1195(1): 198–212. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05453.x

- Pocock MJ, Chapman D, Sheppard L, Roy H (2014) Choosing and Using citizen science: a guide to when and how to use citizen science to monitor biodiversity and the environment. NERC/Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, Wallingford, 1–24.

- Pocock MJO, Tweddle JC, Savage J, Robinson LD, Roy HE (2017) The diversity and evolution of ecological and environmental citizen science. PLoS ONE 12(4): e0172579. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0172579

- Price-Jones V, Brown PMJ, Adriaens T, Tricarico E, Farrow RA, Cardosa AC, Gervasini E, Groom Q, Reyserhove L, Schade S, Tsinaraki C, Marchante E (2021) Citizen Science projects on Alien Species in Europe. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4719259 [dataset]

- Probert AF, Wegmann D, Volery L, Adriaens T, Bakiu R, Bertolino S, Essl F, Gervasini E, Groom Q, Latombe G, Marisavljevic D, Mumford J, Pergl J, Preda C, Roy HE, Scalera R, Teixeira H, Tricarico E, Vanderhoeven S, Bacher S (2022) Identifying, reducing, and communicating uncertainty in community science: A focus on alien species. Biological Invasions 24: 3395–3421. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-022-02858-8

- R Core Team (2022) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/

- Reyserhove L, Desmet P, Oldoni D, Adriaens T, Strubbe D, Davis AJS, Vanderhoeven S, Verloove F, Groom Q (2020) A checklist recipe: Making species data open and FAIR. Database (Oxford) 2020: 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1093/database/baaa084

- Roy HE, Rorke SL, Beckmann B, Booy O, Botham MS, Brown PMJ, Harrower C, Noble D, Sewell J, Walker K (2015) The contribution of volunteer recorders to our understanding of biological invasions. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. Linnean Society of London 115(3): 678–689. https://doi.org/10.1111/bij.12518

- Roy H, Groom Q, Adriaens T, Agnello G, Antic M, Archambeau A-S, Bacher S, Bonn A, Brown P, Brundu G, López B, Cleary M, Cogălniceanu D, de Groot M, Sousa TD, Deidun A, Essl F, Pečnikar ŽF, Gazda A, Gervasini E, Glavendekic M, Gigot G, Jelaska S, Jeschke J, Kaminski D, Karachle P, Komives T, Lapin K, Lucy F, Marchante E, Marisavljevic D, Marja R, Torrijos LM, Martinou A, Matosevic D, Mifsud C, Motiejūnaitė J, Ojaveer H, Pasalic N, Pekárik L, Per E, Pergl J, Pesic V, Pocock M, Reino L, Ries C, Rozylowicz L, Schade S, Sigurdsson S, Steinitz O, Stern N, Teofilovski A, Thorsson J, Tomov R, Tricarico E, Trichkova T, Tsiamis K, van Valkenburg J, Vella N, Verbrugge L, Vétek G, Villaverde C, Witzell J, Zenetos A, Cardoso AC (2018) Increasing understanding of alien species through citizen science (Alien-CSI). Research Ideas and Outcomes 4: e31412. https://doi.org/10.3897/rio.4.e31412

- Schade S, Tsinaraki C (2016) Survey report: data management in Citizen Science projects. Publication Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. Technical report, 1–56.

- Schade S, Tsinaraki C, Roglia E (2017) Scientific data from and for the citizen. First Monday 22. https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v22i8.7842

- Schade S, Kotsev A, Cardoso AC, Tsiamis K, Gervasini E, Spinelli F, Mitton I, Sgnaolin R (2019) Aliens in Europe. An open approach to involve more people in invasive species detection. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems 78: 101384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2019.101384

- Seebens H, Blackburn TM, Dyer EE, Genovesi P, Hulme PE, Jeschke JM, Pagad S, Pyšek P, Winter M, Arianoutsou M, Bacher S, Blasius B, Brundu G, Capinha C, Celesti-Grapow L, Dawson W, Dullinger S, Fuentes N, Jäger H, Kartesz J, Kenis M, Kreft H, Kühn I, Lenzner B, Liebhold A, Mosena A, Moser D, Nishino M, Pearman D, Pergl J, Rabitsch W, Rojas-Sandoval J, Roques A, Rorke S, Rossinelli S, Roy HE, Scalera R, Schindler S, Štajerová K, Tokarska-Guzik B, van Kleunen M, Walker K, Weigelt P, Yamanaka T, Essl F (2017) No saturation in the accumulation of alien species worldwide. Nature Communications 8(1): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14435

- Seebens H, Bacher S, Blackburn TM, Capinha C, Dawson W, Dullinger S, Genovesi P, Hulme PE, Kleunen M, Kühn I, Jeschke JM, Lenzner B, Liebhold AM, Pattison Z, Pergl J, Pyšek P, Winter M, Essl F (2020) Projecting the continental accumulation of alien species through to 2050. Global Change Biology 27(5): 97–982. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15333

- Silvertown J (2009) A new dawn for citizen science. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 24(9): 467–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2009.03.017

- Swinnen K, Vercayie D, Vanreusel W, Barendse R, Boers K, Bogaert J, Dekeukeleire D, Driessens G, Dupriez P, Jooris R, Steeman R, Van Asten K, Van Den Neucker T, Van Dorsselaer P, Van Vooren P, Wysmantel N, Gielen K, Desmet P, Herremans M (2018) Waarnemingen.be: Non-native plant and animal occurrences in Flanders and the Brussels Capital Region, Belgium. BioInvasions Records 7(3): 335–342. https://doi.org/10.3391/bir.2018.7.3.17

- Trichkova T, Paunović M, Cogălniceanu D, Schade S, Todorov M, Tomov R, Stănescu F, Botev I, López-Cañizares C, Gervasini E, Hubenov Z, Ignatov K, Kenderov M, Marinković N, Mitton I, Preda C, Spinelli FA, Tsiamis K, Cardoso AC (2021) Pilot Application of ‘Invasive Alien Species in Europe’ Smartphone App in the Danube Region. Water (Basel) 13(21): 2952. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13212952

- United Nations (1992) Convention on Biological Diversity 28(1–4): 88–103. https://doi.org/10.7882/AZ.1992.018

- United Nations (2019) World Population Prospects 2019, Online Edition. Rev. 1. https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/Population/

- Vanderhoeven S, Adriaens T, D’hondt B, Van Gossum H, Vandegehuchte M, Verreycken H, Cigar J, Branquart E (2015) A science-based approach to tackle invasive alien species in Belgium – the role of the ISEIA protocol and the Harmonia information system as decision support tools. Management of Biological Invasions 6(2): 197–208. https://doi.org/10.3391/mbi.2015.6.2.10

- Vilà M, Basnou C, Pyšek P, Josefsson M, Genovesi P, Gollasch S, Nentwig W, Olenin S, Roques A, Roy D, Hulme PE (2010) How well do we understand the impacts of alien species on ecosystem services? A pan‐European, cross‐taxa assessment. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 8(3): 135–144. https://doi.org/10.1890/080083

- Wiggins A, Crowston K (2011) From Conservation to Crowdsourcing: A Typology of Citizen Science. 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. IEEE, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1109/HICSS.2011.207

- Wilkinson MD, Dumontier M, Aalbersberg IJJ, Appleton G, Axton M, Baak A, Blomberg N, Boiten J-W, da Silva Santos LB, Bourne PE, Bouwman J, Brookes AJ, Clark T, Crosas M, Dillo I, Dumon O, Edmunds S, Evelo CT, Finkers R, Gonzalez-Beltran A, Gray AJG, Groth P, Goble C, Grethe JS, Heringa J, ’t Hoen PAC, Hooft R, Kuhn T, Kok R, Kok J, Lusher SJ, Martone ME, Mons A, Packer AL, Persson B, Rocca-Serra P, Roos M, van Schaik R, Sansone S-A, Schultes E, Sengstag T, Slater T, Strawn G, Swertz MA, Thompson M, van der Lei J, van Mulligen E, Velterop J, Waagmeester A, Wittenburg P, Wolstencroft K, Zhao J, Mons B (2016) The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data 3(1): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18

- Williams LA, DeSteno D (2008) Pride and perseverance: The motivational role of pride. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 94(6): 1007–1017. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.94.6.1007